The U.S. Army has always had a complicated relationship with men like Joe Ronnie Hooper.

When the shooting starts, they’re priceless.

When the shooting stops, they’re a problem.

Hooper wasn’t misunderstood by the Army. He was fully understood. Leadership knew exactly what he was—volatile, undisciplined, aggressive, unreliable in garrison, unstoppable in combat. The institution made a conscious choice, over and over again, to tolerate behavior that would have ended almost anyone else’s career because Hooper delivered something the Army needed more than compliance: results under fire.

That bargain carried a cost. And in Hooper’s case, it didn’t come due until the war was over.

Built for War, Not for the Army

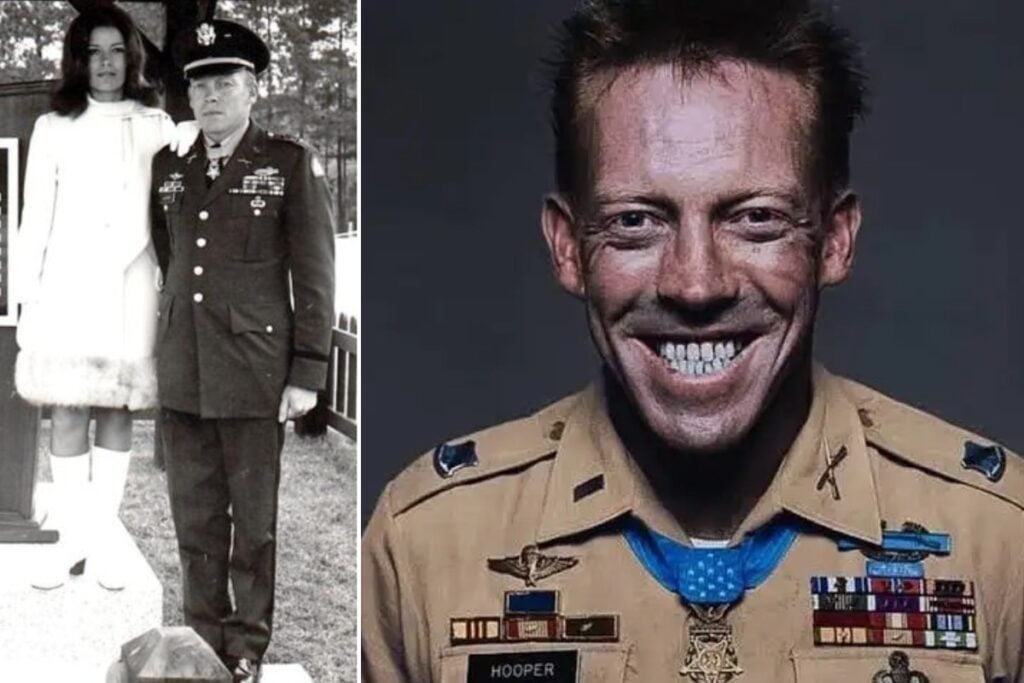

Hooper’s early life reads like the origin story of a soldier who was never going to thrive in a peacetime bureaucracy. Born in 1938 in Piedmont, South Carolina, and raised in Moses Lake, Washington, he wasn’t groomed for command or credentials. He barely cleared the educational minimums to stay in uniform at all.

He joined the Navy first, served aboard aircraft carriers, and left honorably—but restlessness followed him. By 1960 he was in the Army, airborne-qualified, infantry-bound, and chasing the hardest units available. Korea. Fort Bragg. Fort Hood. Fort Campbell.

From the start, two parallel records followed him everywhere:

- Combat evaluations that praised his aggression and leadership under pressure

- Disciplinary paperwork that showed missed formations, AWOL incidents, and repeated nonjudicial punishment

Panama exposed the fault line. As a platoon sergeant, Hooper stacked Article 15s, went AWOL more than once, and ultimately received a summary court-martial that reduced him to corporal. In any modern Army, that’s the end of the road. Even in the 1960s, it should have been.

Instead, the Army reassigned him to the 101st Airborne Division.

That decision wasn’t charity. It was calculated.

Huế: When the Army Cashed the Check

The Battle of Huế wasn’t a cinematic firefight—it was block-by-block, bunker-to-bunker slaughter. On February 21, 1968, Hooper was a squad leader in Delta Company, 2nd Battalion (Airborne), 501st Infantry.

What followed is one of the most violent individual actions ever recorded in U.S. infantry combat.

Hooper repeatedly crossed open ground under machine-gun and rocket fire. He assaulted enemy bunkers alone. He pulled wounded soldiers to safety while already wounded himself. He killed enemy fighters at bayonet distance. He refused evacuation until his men were reorganized and the position secured.

By the end of the day, Hooper was credited with 22 enemy killed—out of 115 confirmed kills across the war. He had been wounded yet again. His body was failing, but his unit held.

The Army awarded him the Medal of Honor not because he was disciplined, polished, or professional in the modern sense—but because he was exactly the kind of man you need when nothing else is working.

The Decorations Didn’t Fix the Man—or the Institution

Hooper returned from Vietnam and was discharged in 1968. That alone should tell you something. Even with a Medal of Honor pending, the Army didn’t know what to do with him.

He reenlisted anyway. Served in public affairs—an almost surreal assignment for a man whose reputation was built on violence. President Richard Nixon presented him the Medal of Honor in 1969, but the ceremony didn’t translate into stability.

Hooper fought his way back into infantry roles. Deployed again to Vietnam. Served as a pathfinder. Led platoons. Took a direct commission to second lieutenant.

And then reality set in.

The post-Vietnam Army was changing. Professional military education mattered. Degrees mattered. Clean records mattered. Hooper had none of those. He wanted a full career. The Army forced him out of active duty instead.

Even in the reserves, the pattern held. Spotty attendance. Administrative friction. A final separation in 1978—even though he’d been promoted to captain.

The institution had extracted everything it needed from him. There was no longer room for the rest.

The Personal Cost No One Likes to Include

This is where most official biographies stop.

They don’t talk about the drinking. They don’t talk about the anger. They don’t talk about how Vietnam veterans—especially the most violent ones—were treated when they came home.

Accounts from those who knew Hooper describe a man who was likable, charismatic, and deeply troubled. He related to veterans. He partied hard. He drank heavily. He was bitter about the war and the way the country turned its back on the people who fought it.

He died in 1979, alone in a Louisville hotel room, from a cerebral hemorrhage. He was forty years old.

No parade. No institutional reckoning. Just another combat-exhausted body that the system didn’t know how to keep alive once the shooting stopped.

Why Joe Ronnie Hooper Still Matters

Hooper’s story isn’t inspiring in the way recruiting commands like. It’s unsettling—and that’s why it matters.

He forces an honest conversation the Army still avoids:

What happens when the traits that win wars make someone incompatible with the institution that sent them to fight?

Hooper wasn’t an aberration. He was a preview.

The Army tolerated his UCMJ violations because he delivered lethal outcomes. When the war ended, tolerance ended with it. The medals stayed. The support didn’t.

You don’t have to excuse his misconduct to acknowledge his contribution.

You don’t have to sanitize his life to respect his courage.

Joe Ronnie Hooper was a devastatingly effective infantryman, a disciplinary nightmare, and a casualty of the same system that elevated him.

That contradiction isn’t a flaw in his legacy.

It is his legacy.

Editor’s Note: This article relies on publicly available service records, historical reporting, and contemporaneous accounts to examine the full arc of Captain Joe Ronnie Hooper’s military career and post-service life. Where context is provided regarding institutional culture, disciplinary tolerance, or personal struggles common among Vietnam-era combat veterans, it is offered as historical analysis—not as a definitive assessment of individual intent, mental health, or causation.

The Salty Soldier does not speculate beyond the available record, nor does it diminish Captain Hooper’s valor or sacrifice in combat. Rather, this piece aims to present a complete and honest account of a complex soldier whose service reflects broader realities of war, command decisions, and post-conflict transition.

© 2026 The Salty Soldier. All rights reserved.