Editor’s Note: This guest article reflects the author’s reporting and analysis. It addresses a disputed historical event and draws on on-the-record interviews and publicly available sources. The Salty Soldier does not independently adjudicate competing accounts related to the Abbottabad raid.

By Benjamin Reed

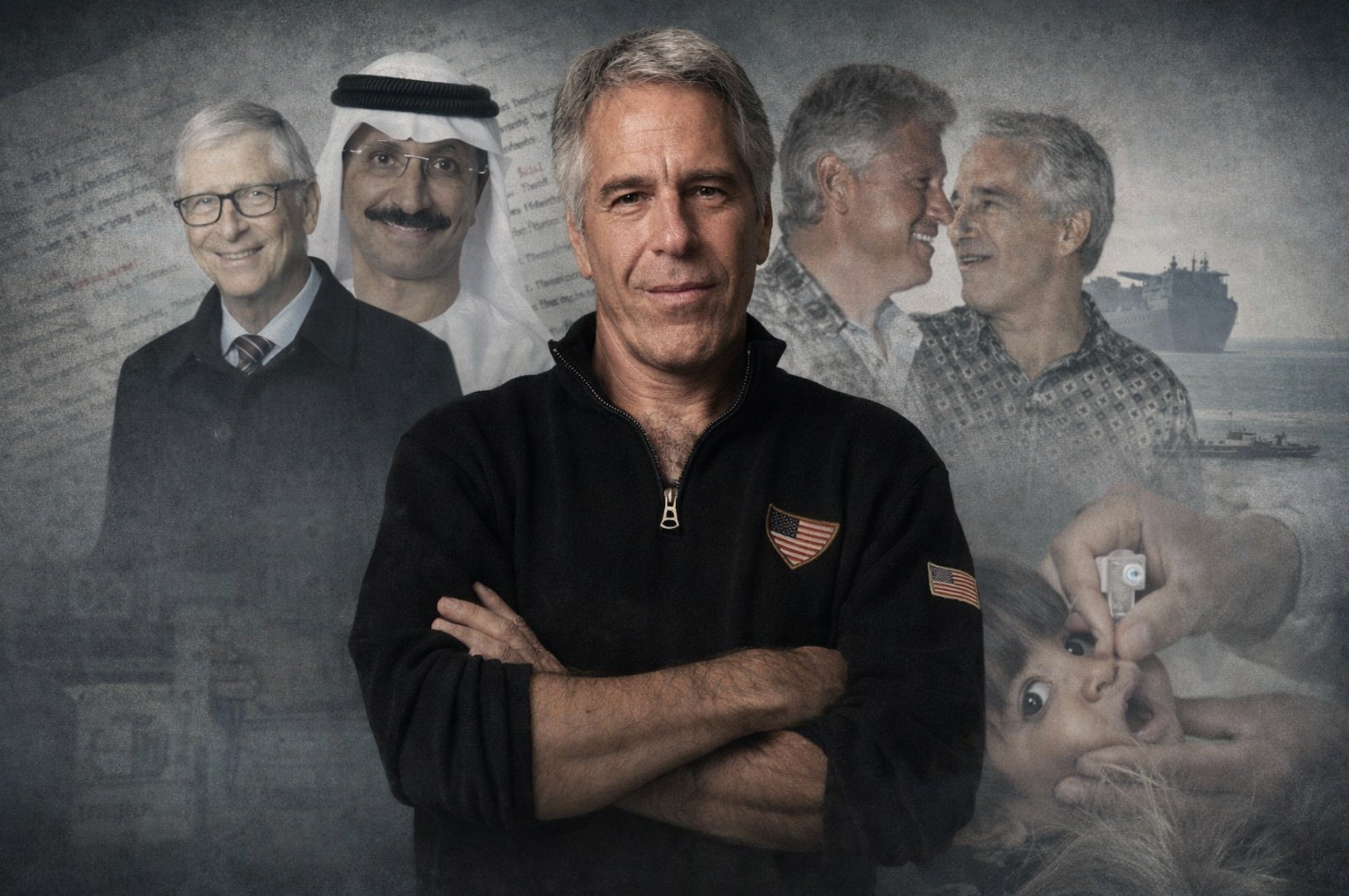

I spoke with Rob O’Neill recently about a dispute that, more than a decade after the Abbottabad raid, continues to resurface. Our conversation was prompted by a defamation lawsuit he filed in late 2025, seeking $25 million in damages from Brent Tucker and Tyler Hoover, the founders of the Anti-Hero Podcast. O’Neill alleges that years of insinuation, selective clip editing, and public doubt broadcast to large audiences caused reputational harm and personal strain, including effects on his family.

That lawsuit is why the Abbottabad raid is being discussed again. Not because new evidence has emerged, but because a narrow historical disagreement has been expanded into a broader credibility trial.

The dispute over the Abbottabad raid has taken on a strange afterlife. What began as a disagreement over seconds inside a darkened room has metastasized into a public referendum on credibility, conducted almost exclusively by people who were not present. No member of the raid team has publicly challenged Rob O’Neill’s account. The result has been less inquiry than theater.

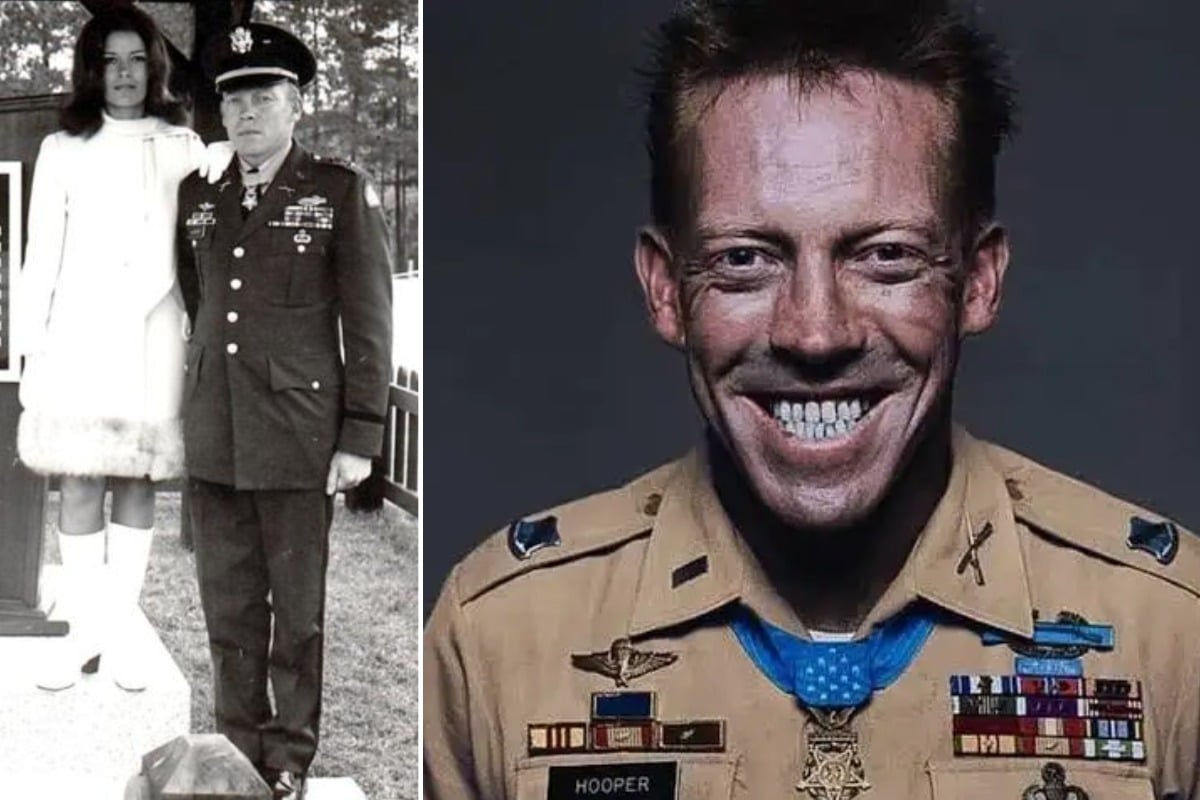

Start with the facts that have never moved. Rob O’Neill was on the mission that killed Osama bin Laden. No serious party disputes that. He moved through the compound. He entered the room. He fired. Bin Laden died. The disagreement, such as it exists, concerns sequence, specifically who fired first in a compressed, chaotic moment, not presence, participation, or outcome.

That disagreement originates from a single source. The only person to offer a materially different account of shot sequence is Matt Bissonnette, who published No Easy Day in 2012 under the pseudonym “Mark Owen.” Even there, the divergence is narrow. Bissonnette has never accused O’Neill of fabricating his role or inventing his presence on the raid. His account differs on timing, not on who was in the room or what ultimately happened.

Bissonnette’s account entered the public record through an unauthorized commercial release while he was still bound by nondisclosure agreements, resulting in financial penalties imposed by the Department of Defense. By the time O’Neill’s account appeared in any form, participant narratives were already public, and the premise of total silence had been broken by someone else.

Rob O’Neill’s account has not changed. Across interviews, print profiles, and long-form conversations over more than a decade, he has described his role in consistent terms.

It is also important to be precise about how O’Neill entered the public record. He did not seek public attention for his role in the raid. When he first spoke to the press, he did so anonymously. In 2013, Esquire published a long-form profile of a SEAL involved in the Abbottabad operation without naming him. The article focused on the difficulties of leaving service, physical wear from years of combat, and the strain placed on families after long wars.

O’Neill did not identify himself, promote a book, or attempt to monetize the mission. His anonymity was later undone by an inadvertent disclosure by a family member. That disclosure had consequences. Once his name entered the public domain, it could not be recalled. Exposure of that kind does not merely invite attention; it alters personal security, places a target on one’s back, and reshapes the boundaries of private life in ways that are difficult to reverse.

O’Neill’s professional record matters here. He served more than sixteen years as a Navy SEAL, deploying with SEAL Team Two, SEAL Team Four, and later DEVGRU. His career spanned the most intense period of the post September 11 wars and included numerous high risk operations beyond Abbottabad. The raid did not define his service, but it has come to dominate his public identity.

In recent years, scrutiny intensified. Veteran media and long-form podcasts reframed a narrow historical disagreement into a broader credibility trial. The Anti-Hero Podcast became a central platform in that shift. Its hosts, Tucker and Hoover, neither of whom were on the raid or part of the unit involved, positioned themselves as arbiters of truth.

That posture became harder to sustain as the show itself began to fracture. Hoover later stepped away from the podcast amid questions surrounding his own professional record from his time in law enforcement, following his departure from a sheriff’s department under internal review. Those matters are separate from Abbottabad, but they complicate the authority with which he claimed to assess the credibility of others. A public role built on adjudicating truth carries weight only insofar as the standards applied outward are met inward as well.

I have observed a similar dynamic firsthand. After returning from Ukraine, where I served alongside Ukrainian forces, I watched how secondhand commentary can accrue authority in the absence of direct involvement. The pattern is familiar.

Over time, the effects extended beyond abstract debate. In authorized conversations with me, O’Neill described how sustained public doubt altered the terms of his public life. His professional reputation is inseparable, for better or worse, from a single historical event. When that event is repeatedly framed as suspect, the consequences are no longer abstract.

More difficult still has been the impact on his family. His children are now old enough to read what is written online. They see comments questioning their father’s integrity. They encounter strangers confidently undermining a role he lived, carried, and then tried to leave behind. These are not disagreements over policy or personality. They are challenges to how a family understands its own history.

This context explains why O’Neill ultimately turned to the courts. The lawsuit does not ask the public to relitigate the raid. It asks whether there are limits to how far secondhand judgment can go before it becomes reputational damage.

The bin Laden raid was not a morality play. It was a military operation carried out by a team under orders. Every man on that mission shares responsibility for its success. O’Neill has never claimed sole ownership of the outcome. He has claimed, consistently, that he was there. The record supports that claim.

There is also a broader point worth stating plainly. We should be careful about cultivating a culture that rewards sharpshooting fellow veterans over events those critics did not witness. Scrutiny has its place. It is sometimes necessary. But it loses legitimacy when it becomes detached from proximity, responsibility, and cost.

Men who carry out missions like Abbottabad do so in silence, at night, and at distance from public life. They accept the moral and personal burden of violence so others do not have to. When the work is done, they return home with little control over how that service will later be interpreted, edited, or repackaged by people who were never there.

If we believe veterans should be accountable, we should also believe they are entitled to speak for themselves about what they did and what they saw. This case does not call for more suspicion layered onto secondhand commentary. It calls for restraint, proportion, and an understanding of where authority properly resides.

Rob O’Neill was there. His account has not changed. At some point, that should be enough.

Benjamin Reed is a U.S. Army veteran who served in Iraq, later worked as a contractor in Afghanistan, and joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces following Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. He is a columnist with SOFREP and the author of the forthcoming memoir War Tourist, represented by Writers House Literary Agency. He writes on war, veterans’ issues, and modern conflict from lived experience.

© 2026 The Salty Soldier. All rights reserved.